Gap Analysis: Surviving and Thriving with a New Project

Welcome to your new project!

It’s your first day on a new project, maybe with a new organisation. Your new boss is relieved and delighted to see you. You get offered a cup of coffee and are sat down in a meeting room. You sense that expectations are really high. After a polite welcome, your boss starts to uncover some specifics about the project.

Ah, pity you could not come sooner!

The project schedule has been slipping the last 3 months.

We still need to deliver on time though!

Sven, the Systems Engineer, left last week

There are a few problems, but you’re a project manager, right?

[You do have superpowers, don’t you?]

Good luck, … oh, and when can you show me your project plan – by Friday, maybe?

You are parachuting into a new organisation and a new project. You have done it several times before. Your boss gives you a distinctively insecure feeling. You know instantly that you need to get to grips with the project. Since you are experienced, you know that there is a “gap” of know-how and understanding that you need to identify and close. Your first challenge is that you don’t know what you don’t know. This challenge is that your boss and the rest of the organisation do not know what they do know! They know the following:

The technology

The organisational systems

The industry standards

The customers

The organisation and people in it

The product range

The terminology and acronyms

The project and the product to be developed

The suppliers

The power structure in the organisation

The organisational culture and way of working

The tools

We can call this the ‘A’ List – just a high-level, generic definition.

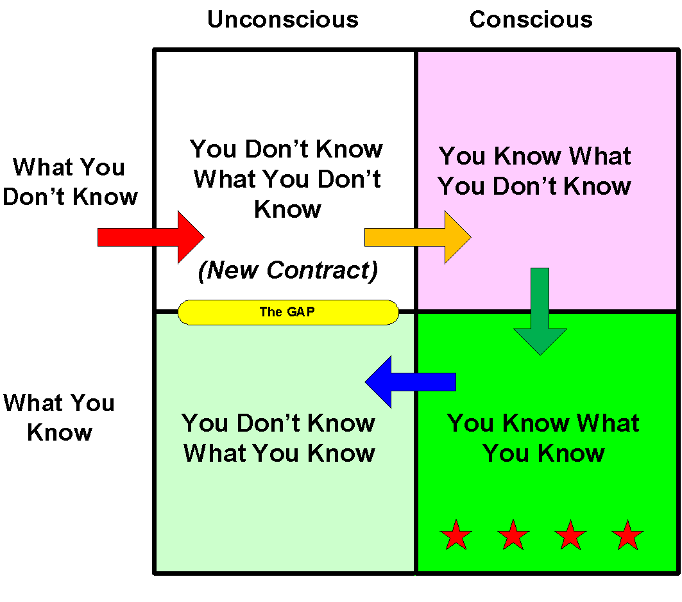

The issue is that your boss and the organisation have been in the organisation so long, that they do not realise what they do actually know, and what new people to the organisation do not know. Unfortunately, telepathy does not work in project management! Your first challenge can be represented in the following diagram.

Your boss apologises after 30 minutes and says he needs to leave for the next meeting. You realise immediately that you have a big challenge. Solving that challenge starts with realising that you are in the first zone, that is, you don’t know what you don’t know.

Your ultimate challenge is that you need to get to the third zone, where you know what you know. More specifically, it is a zone where you know what you need to know, in order to run a successful project. The intermediate stepping stone is finding out what you don’t know.

Getting to Know What You Don’t Know: Your First Challenge

The first thing is to realise that there is a lot to learn! One smart way to start the process is to have a ready-made checklist of at least high-level areas. A good starting point is the ‘A’ List mentioned in the previous section. Over time, you can generate your own generic list of questions. If you would like to kick-start your own checklist, just DM me on LinkedIn.

The project manager’s skill at asking searching questions is indeed a vitally important skill. They can be open questions or closed questions or a combination of the two. To be established early is, who knows what?

Questions can be targeted at:

The project set-up and the project lifecycle

The project organisation

The development progress, strategy and plan

The business rationale

The ability of the organisation to deliver projects

Once the project manager has mapped out things that he does not know, it then is a matter of establishing a real view of the project by discussion and sometimes interrogation. A conversational style of discussion is received best by the project team, its stakeholders and key organisational players. It is also advisable to spread the ‘interrogation’ amongst a number of individuals.

Formal project documentation should also help.

Project definition:

Requirements Specification

PID

SoW

System Design Specification

Alternatively

Business Case

Project Charter

A review of these formal documents may also lead to follow-up questions about the project, the project organisation and responsibilities, plus the business justification, rationale and benefits.

A new project manager needs to orientate him or herself to the project rapidly. Eventually, we transition from:

Zone 1: Not knowing what we don’t know, then to

Zone 2: Knowing what we don’t know

Zone 3: Knowing what we do know

These transitions are rarely clear cut and tend to be gradual. However, with a systematic and structured approach, the familiarisation will be rapid. Once we are in Zone 3 of the familiarisation process, we will be in a far better position to manage the project.

An important factor is that while moving through the process we are building our project network and forming valuable relationships.

However, there may be added challenges!

Discovering What the Organisation Doesn’t Know: A Second Potential Challenge.

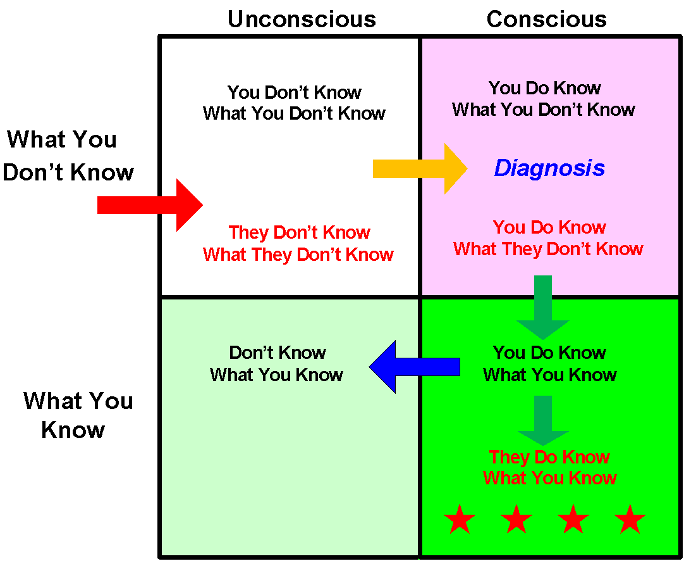

The first challenge was what you don’t know. Through experience at parachuting into new projects, as battle-hardened project managers, we often experience the situation that the organisation is unaware about:

Weaknesses in the project set-up

Weaknesses in the product design

Flaws in the business case

Weaknesses in the organisations functioning and ability to deliver complex projects

The initial transition diagram can be augmented by what the organisation does not realise.

This indeed can create a very challenging situation, because no one will or can tell you what the problems are. You need to find it out by investigation. The challenges fall into two generic categories:

The Content of the Project: We can call these “normal challenges”, which relate to the project definition

The Context of the Project: We can call these “supranormal challenges”, which relate to the organisation, processes, customers and suppliers

Either of these categories can adversely affect the project which you have been assigned. Let’s look at some specific examples of challenges that nobody is aware of or is a known weakness that is ignored:

The defined product has too many variants to be developed, which is going to swamp the development team and delay product release

There is a severe lack of system engineering resources

The customer has not been briefed in change control procedures

A new supplier has never been used before, and the release criteria are not yet clear

The architectural design has flaws in it because it has not been reviewed by all necessary engineering disciples

The project team is currently dysfunctional and will need strong leadership

The project management system is sub-optimal

Release checklists are vague, out-of-date or invalid

The organisation does not have enough compute power to simulate product functionality and behaviour

Some new versions of CAE software have numerous bugs

The method of work estimation is inadequate

The full scope of the work that needs doing is not fully identified

It is possible to formulate a list of common project failure modes. These can be checked by the project manager in the first one to three weeks of his or her new assignment. In general, the earlier you identify project failure modes, the better chance you have of:

Avoiding the problem altogether

Mitigating the problem – reducing its severity

Finding workarounds

Conclusion

Modern high-tech system development is extremely challenging. The system itself may be difficult to design, build, verify and validate. However, factors which affect key project parameters of Scope, Schedule, Cost and Quality can relate to the project formulation, the processes in-place or the organisational context.

Super Project Managers are on the look out for specific project failure modes the minute they walk through the door. They rapidly form and develop their network of contacts, and form relationships. Skilful questioning is a key skill. Identifying, collaborating and coordinating solutions requires super communication skills – something an effective project manager must develop.